I’ve recently been putting together a bunch of related thoughts about how I do some parts of systems analysis and design. They involve bringing order to collections of items, data, actions, and ideas. I’ve written about one of the ideas explicitly before and touched on a couple of others. Here I wanted to go into detail.

Collections and Systems

So what are we trying to bring order to? Writing from the point of view of a business analyst or systems analyst it’s clear that this comes up in the course of our work. The collections of stuff we run into are part of the systems we are called upon to analyze, build, and improve.

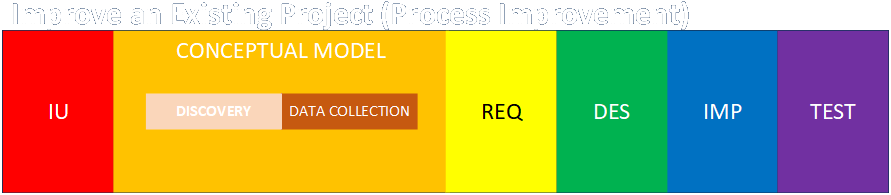

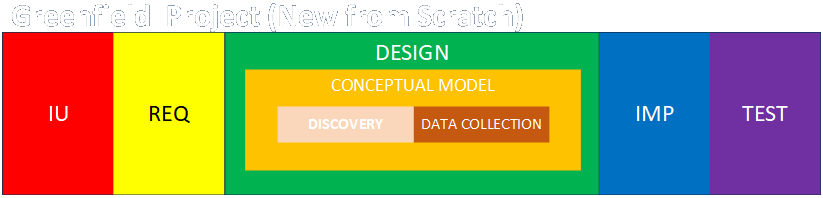

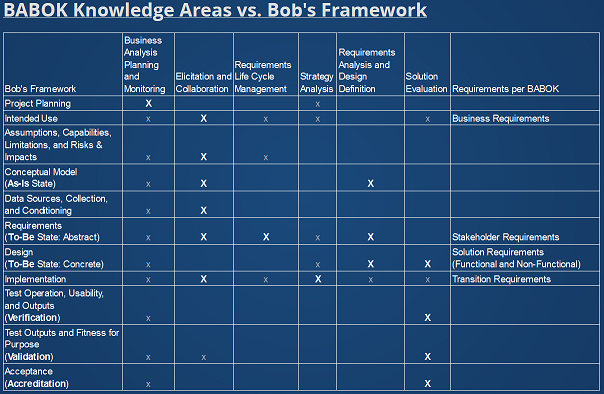

The raw material of our analyses is gathered through various processes of discovery (identifying the nouns and verbs of what’s going on, see here, here, here, here, and here), and data collection (identifying the adjectives and adverbs that characterize what’s going on, see here, here, and here). As I’ve noted previously, discovery comes first so you know what data you need to collect.

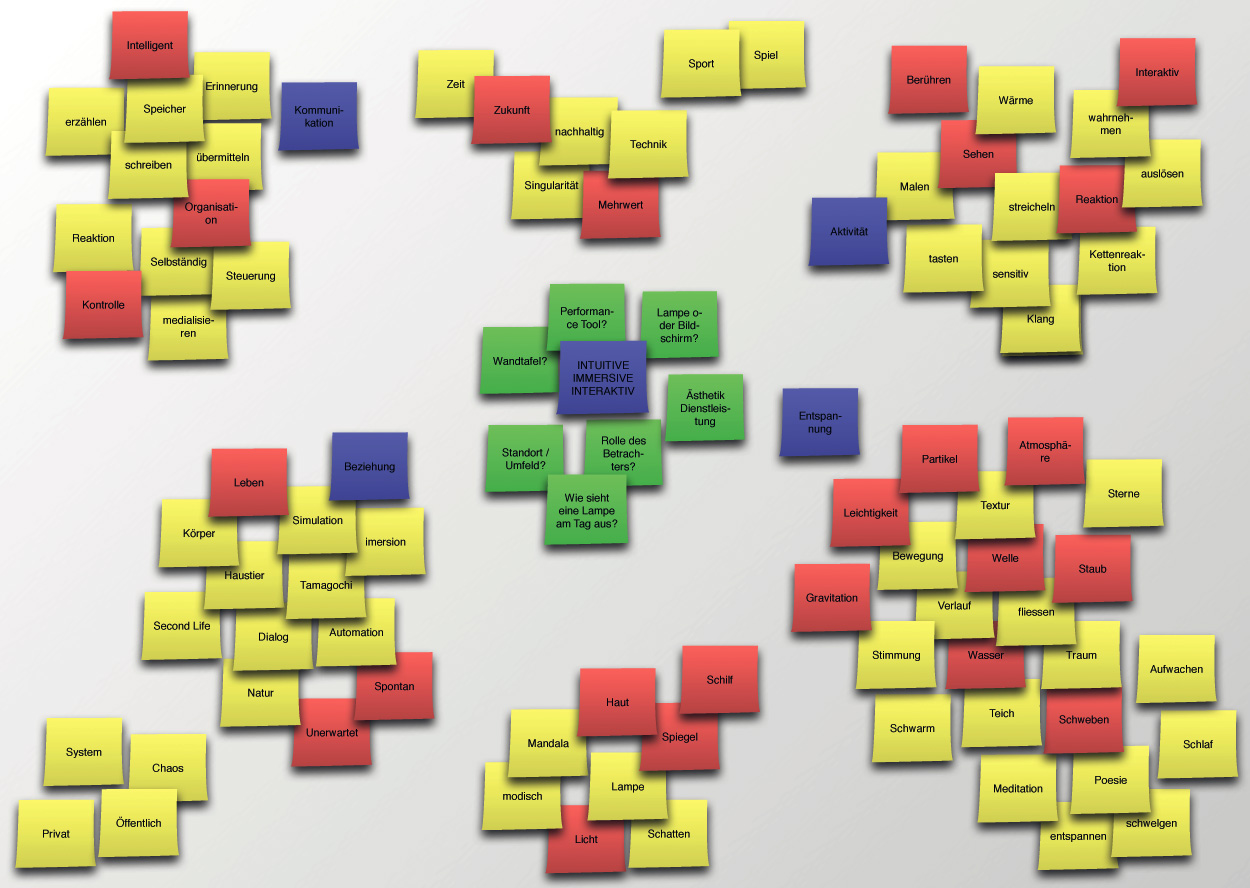

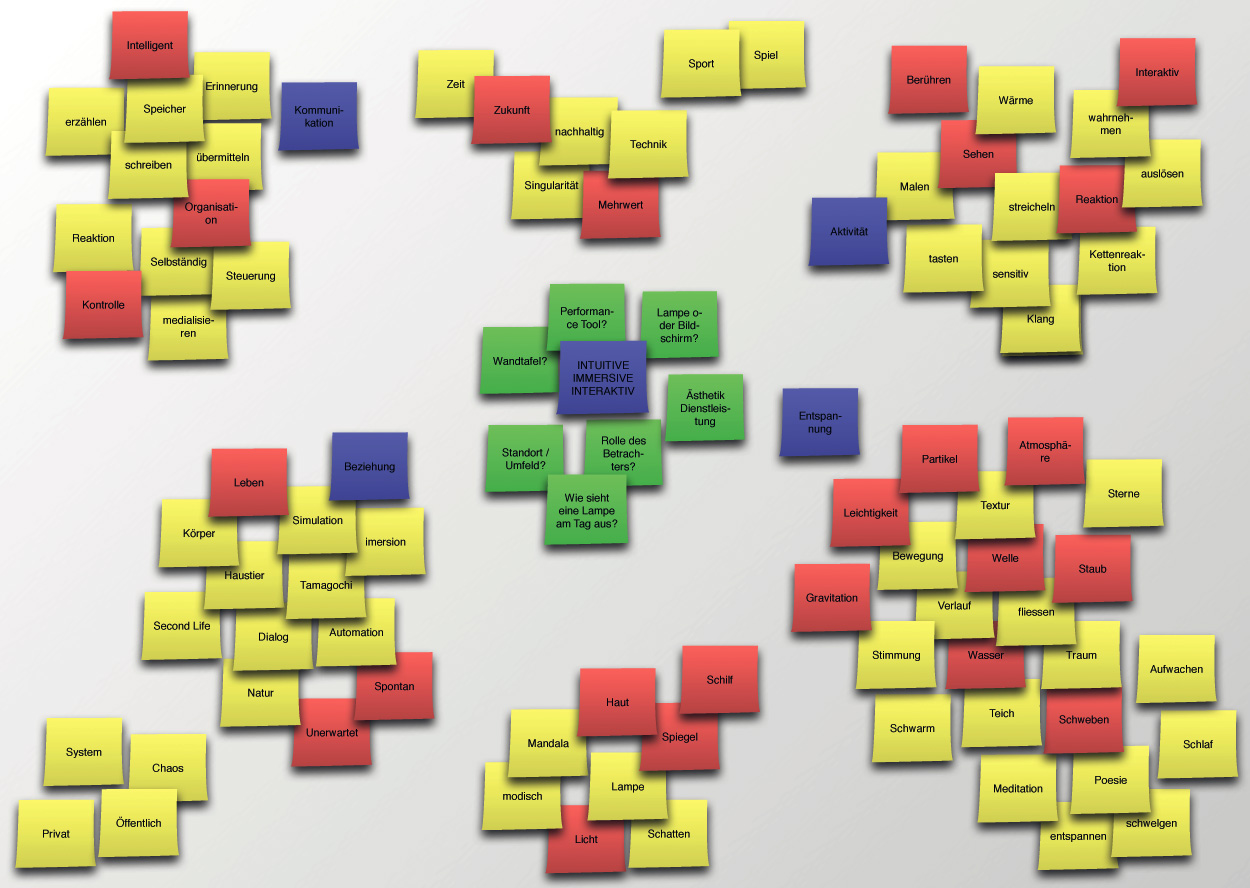

The articles in the links describe many ways analysts learn about the items and processes under study, but I want to add a very important one: brainstorming. This is where people sit together and just vomit out every relevant thought they can about the subject under study. The interesting thing about this technique is that it usually, but not always, involves an associated step of grouping the ideas that seem somehow related.

Finding Commonalities

Here are just a few examples of how people find commonalities.

Frank Bunker and Lillian Moller Gilbreth, whom you may know from the book Cheaper By the Dozen, were pioneers of industrial management and time and motion studies. Through extensive observation they were able to identify a number of simple hand movements that manufacturing workers used in different combinations, and this insight was an important step in making processes more efficient, comfortable, and safe. These basic movements came to be called therbligs, based on reversing the spelling of Frank’s last name.

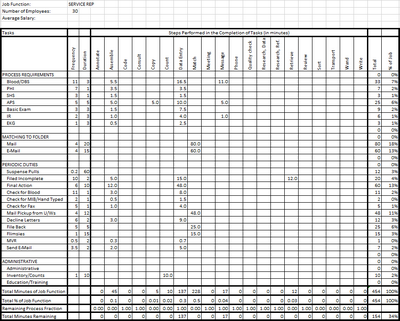

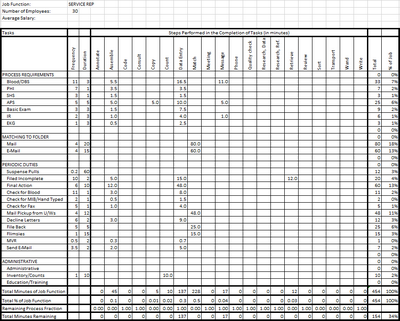

When I did business process reengineering for FileNet implementations, part of the analysis I learned to do involved identifying similar operations that workers performed in different processes (I’ll call these departments) in the operation. The figure below shows an analysis of all operations identified in a particular department (each of which may have involved up to about fifty workers, as I recall), and the time per worker per day spent on each. The rows identify the unique operations performed by the workers in that department, so all rows have data associated with them. The columns characterized the general type of each operation. Since this list included all types of operations performed by workers in all departments of the overall process, not every column had entries for every department, but every column had entries in the grid for at least one department. It was the information in the columns that allowed us to determine which operations could be automated, and thus how much time and money could be saved. It also allowed us to quantify the new operations that had to be added to the reengineered process, the number of workers and computers required, and their ultimate cost.

I often say that a business or systems analyst is a kind of learning machine, since they have to learn the particulars of the specific things they are analyzing, but they also have to be communication and translation machines. That is, they have to be able to talk to a lot of different of people about a lot of different things, and somehow get them to understand each other. The more the analyst knows about everyone’s job and concerns, the better job the analyst can do.

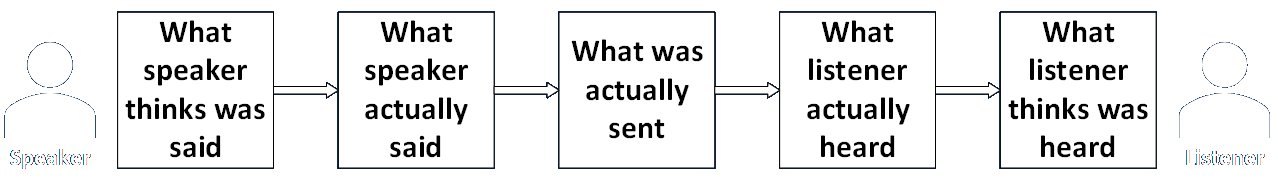

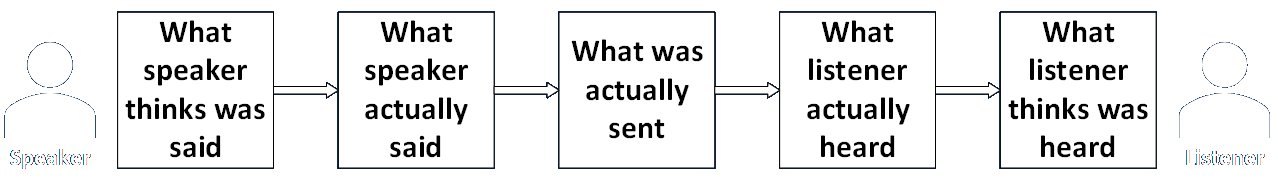

He is a basic communication model I learned in a leadership school in the Army.

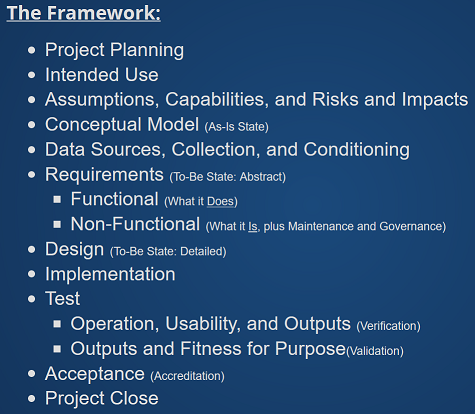

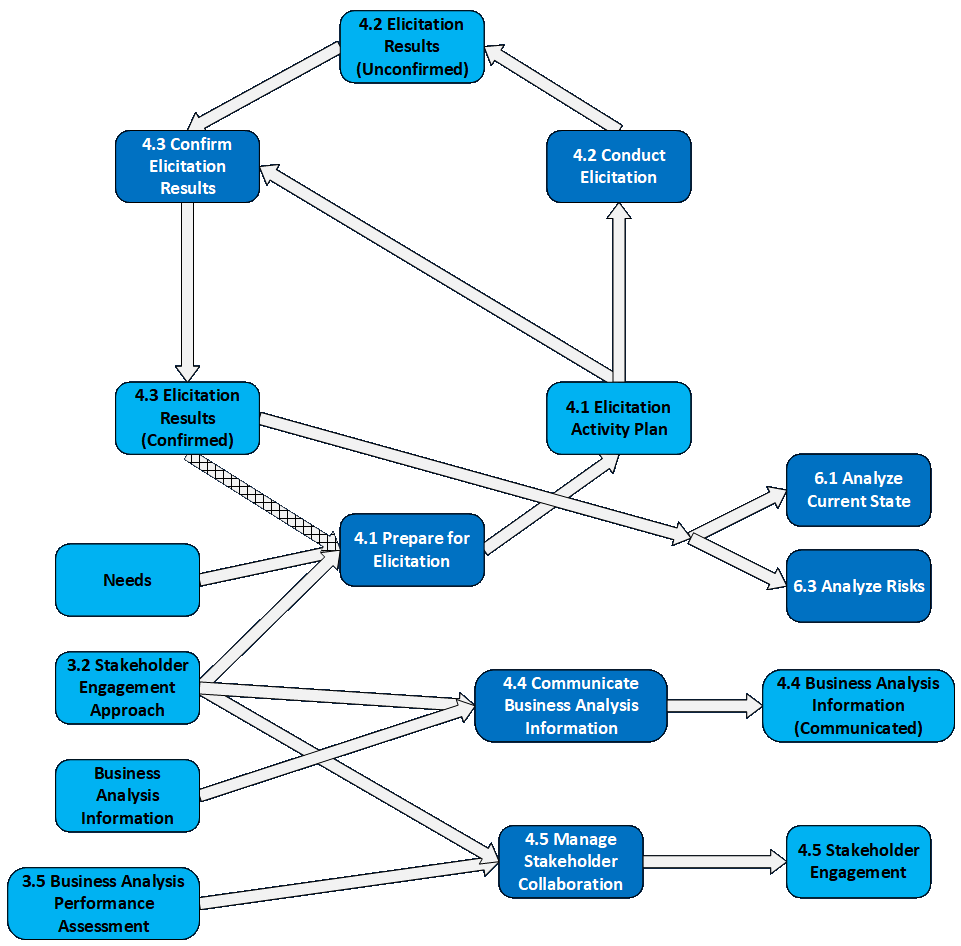

Potentially different techniques can be used to improve each step in the communication process, and this applies whether the communication is in person or electronic. One of the key things is verifying the integrity of each message, and retrying the message as needed until all parties agree that a shared understanding has been achieved. I describe this for electronic communication here (see references to retries), but for people trying to work together through a problem-solving engagement, I refer to the core iterative cycle in my analytic framework, as shown below.

This iterative process helps build understanding, trust, buy-in, and ideally enthusiasm from all participants, and is a form of finding common ground — or commonalities — between people.

Common themes are a hallmark of great literature. While Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon may not be everyone’s idea of great literature, a lot of people think it’s pretty decent science fiction. The story draws parallels between cracking codes in wartime, industrial communications, and interpersonal relationships.

When I was about fourteen I tried to list all the different pieces of Lego I had collected. It wasn’t enough to just list them, though. My precocious, nerdy little self had to try to organize everything into some kind of a taxonomic hierarchy, and that’s where the project hit a snag. Which characteristics would be higher in the hierarchy? Color? Shape? Number and configuration of studs? Height? Something else? I remember that I chose some sort of precedence, but I’m pretty sure I was never really happy with it. Later on I learned about databases, programming, and the ability to sort, display, and analyze flexibly depending on the specific problems at hand. That made me feel a lot better about things.

I didn’t go back, enter all my Lego pieces into an Access database and run a bunch of different reports on them, but these experiences were formative and illuminating. For this conversation, it illustrates that there are many different kinds of commonalities to find. Which ones you find should emerge from the nature of each problem.

The foregoing is an example of there being several possible ways to classify items. By contrast, the Big Five personality traits were identified using only one type of classifying mechanism. As I understand it, they were derived by identifying every possible adjective people can use to describe aspects of a personality, and then a factor analysis was performed on each pair of words (I presume in every combination) to determine the degree to which they were related. When these were analyzed (I don’t profess to know how they did it), the adjectives seemed to fall into five distinct clusters. As someone who’s long been interested in Myers-Briggs personality typing (itself based on the work of Carl Jung), I’ve found this to be quite interesting.

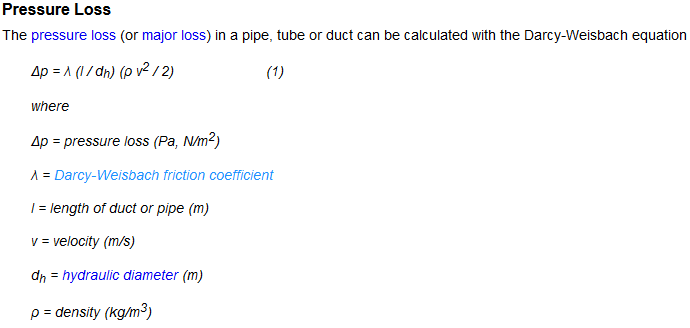

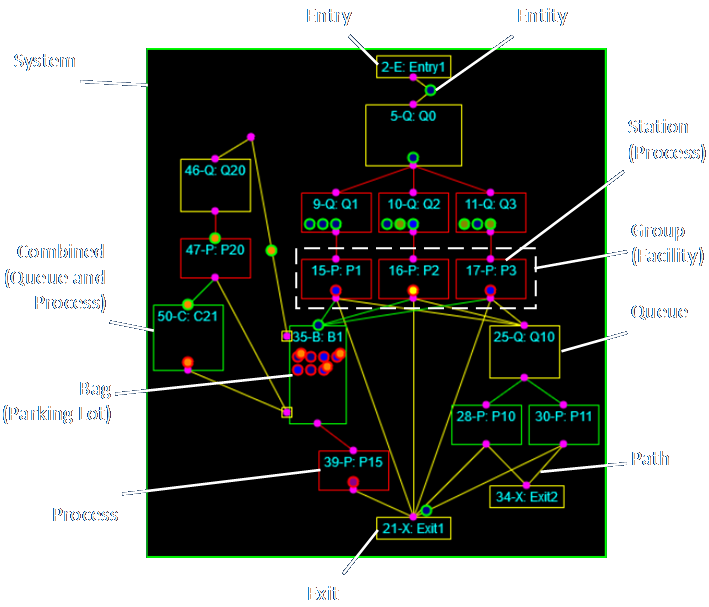

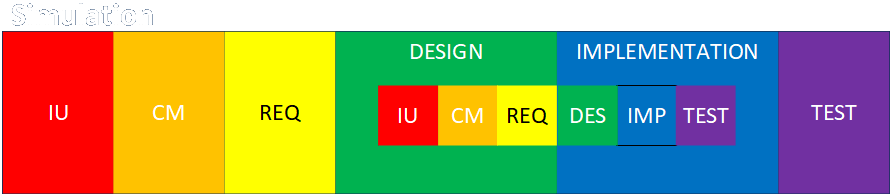

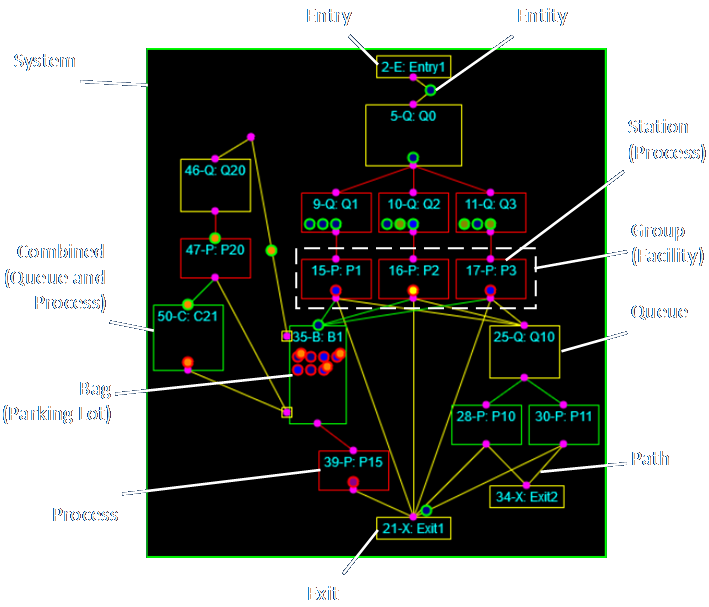

Modularity

As someone who has not only designed and built simulations, but also tools to build simulations, I have a keen appreciation for identifying opportunities to build the smallest number of unique components that can be customized to represent the widest range of entities or processes. I’ve discussed the basic components germane to the creation of discrete-event simulation models here. I documented the creation of my discrete-event simulation demo here, including 91 blog posts. I did something similar when I built a tool to document and calculate coefficients for fluid models.

Being able to identify, design, and implement reusable and reconfigurable components makes systems and architectures much more robust, understandable, documentable, testable, and so on. Said another way, it is a boon to improvement in terms of non-functional requirements.

Rationalization

Finding commonalities can help in the creation of modular designs, but it can bring order to situations in other ways. The best general word I can come up with to describe this process is rationalization. (In a good way, not as Jeff Goldblum’s character invokes the word in the movie The Big Chill.)

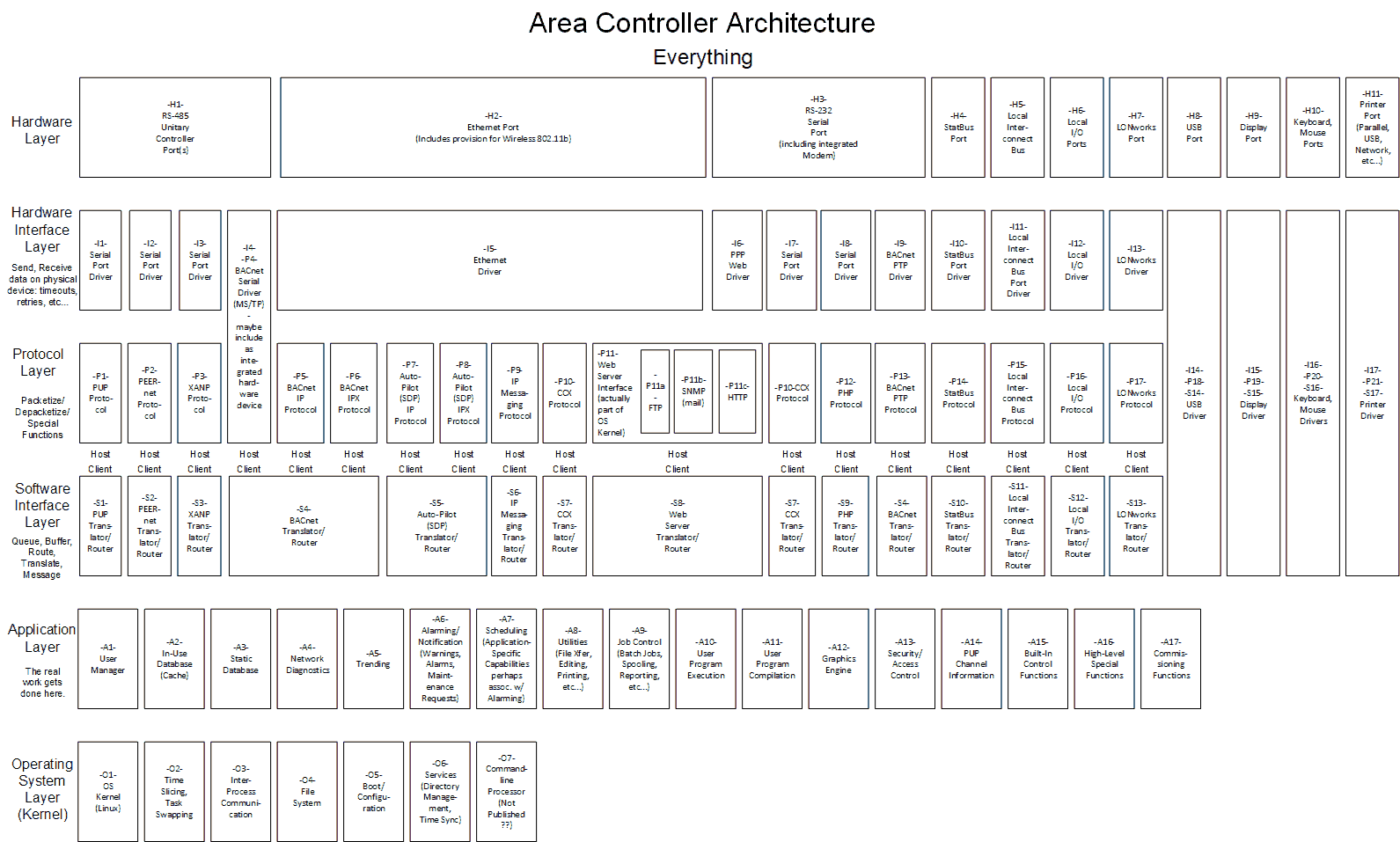

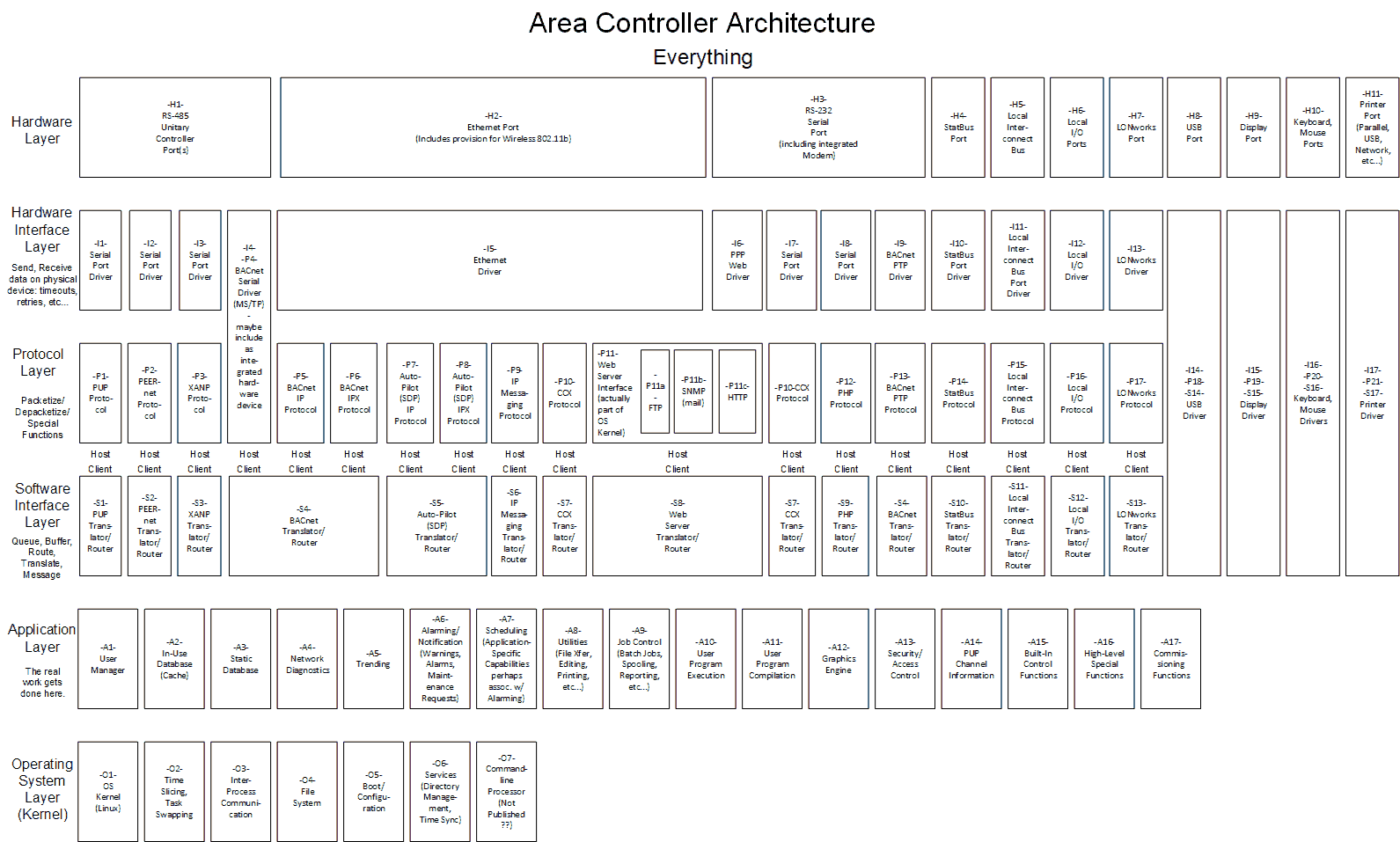

I analyzed the product line of controllers and software for HVAC systems to clearly identify what we had, which existing products should be maintained, which features could be added, and what made sense to develop as new products.

As part of this I identified most pieces of communication and functional capability in two dimensions (heirarchal layers on the vertical, protocol or function on the horzontal) on a Visio drawing, and then I created layers for each product the company made, where the relevant elements could be turned on and off as the analysis proceeded. That pointed to ways to make the existing product line more uniform and where it made sense to add new protocols and develop new products entirely. As I review this now, this could have been accomplished a bit more easily and compactly using a spreadsheet.

Sometimes rationalization just means figuring out ways for people to find things. I describe my proposals for monitoring an entire microservices stack across five levels here. This proposal grew out of the need to make the system understandable and manageable, because it was a total fire drill when anything went wrong, with people needing to scatter all over the place to figure out what was happening. This could have been avoided if the information and tools had been organized and placed in a known location where they could be readily accessed and controlled.

I linked to the discrete-event simulation tool I developed as a proof-of-concept (and proof-that-I-could-develop-in-JavaScript) demo above. Each component was different, but I wanted to ensure they implemented similar features in the same way. Here is one discussion that describes a sliver the process I went through (note that the images are scrollable).

Any form of automation can be thought of as a kind of rationalization, because it tends to make each repetition of an action more consistent and repeatable. If structured properly, this can also help reduce errors, build understanding, and improve situational awareness.

As you can see, rationalization can take many forms. It’s just a form of putting things in order — while simultaneously making them consistent — in a way that make sense for each situation.

Final Thoughts

My desire, when I get the chance to make it happen, is to have other people understand that these processes are similar to those of the iterative customer/team feedback cycle I mention above (and often), in that one is always aware of the full process going in and tries to make use of this knowledge throughout any work effort.

It can take the form of getting practitioners to use similar methods and best practices across different activities, can be supported via internal and external communities of practice, and be facilitated by information shared in meetings and through websites and shared communication portals like Confluence and Slack, among many others.

If you can think of any other examples of how you’ve done this, and what did or didn’t work for you, I’d love to hear about it.