An interview is a process of conducting a conversation with someone to determine what they do, what they need, or how they are reacting to something you’ve given them. The general term elicitation is often used in this context, although elicitation can actually be performed in many contexts, not just interviews.

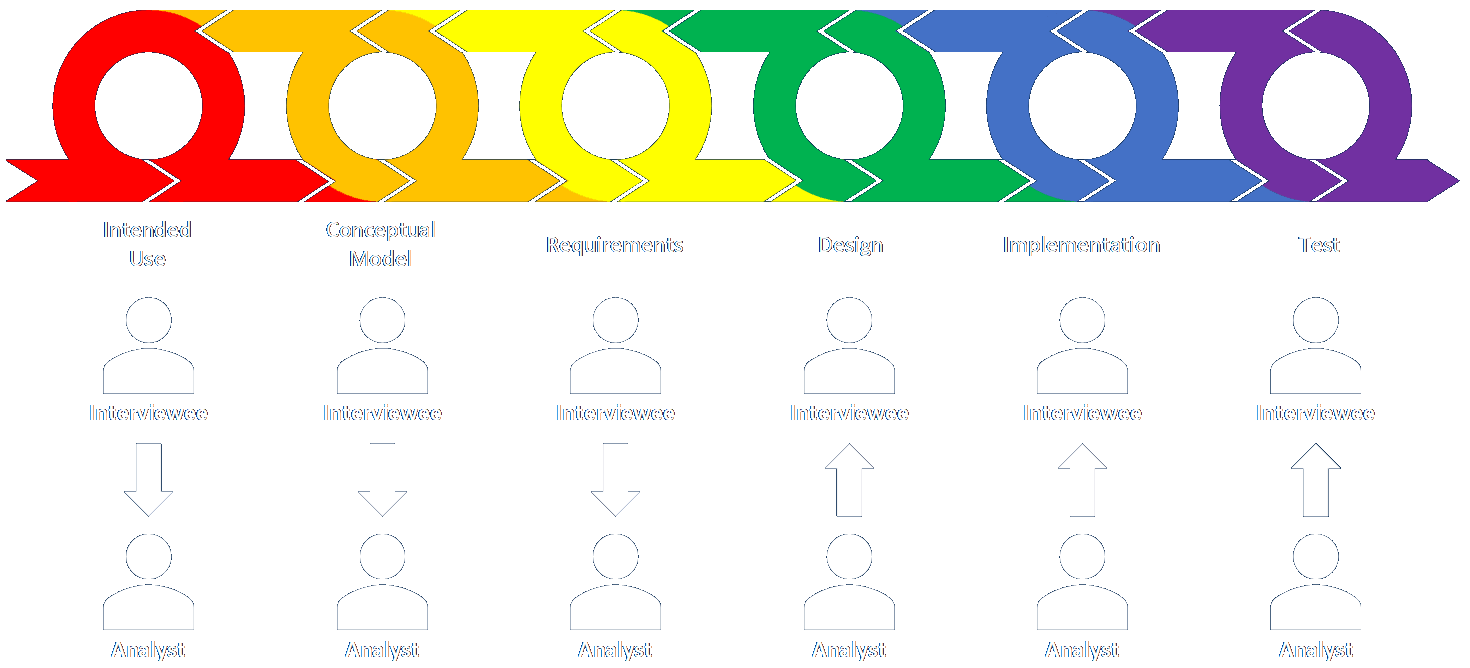

One interesting thing I have found is that the process of elicitation generally flows in different directions during different phases of an engagement. One the one hand, the analyst is always trying to gain information from a practitioner, user, manager, or customer, but in the early stages of an engagement the interviewer is asking questions and receiving answers based on things the interviewee knows or wants but the interviewer doesn’t know. The information flows primarily from the interviewee to the interviewer. In the latter phases of an engagement, the interviewer asks for the interviewee’s reaction to something the interviewer (or the interviewer’s team) has offered to the interviewee. This flow is shown in the following diagram.

Let’s look at how this might work in each of the standard engagement phases.

Intended Use: The interviewee describes the overall goal(s) of the engagement.

Conceptual Model: The interviewee describes the current operations, job functions, customers, sources, technologies, governing rules, and so on.

Requirements: The interviewee identifies the needs of the organization, solution, and customers.

Design: The interviewer offers one or more proposed designs to the interviewee.

Implementation The interviewer offers implemented solution items to the interviewee.

Test and Acceptance The interviewer offers test results to the interviewee.

This is a gross oversimplification for a number of reasons which I will discuss, but this idea seemed interesting enough to write about and share. I would love to hear your thoughts on whether it makes as much conceptual sense as I have felt it does.

In the end, the whole point of my engagement framework is to inspire and structure robust, two-way communication between solution teams and (external and internal) customers. This means that no communication is only one way, one time. It means that communication is iterative and continuous until all parties agree that understanding is thorough and correct and that an appropriate, value-generating course of action is pursued through every phase.

Let’s look at what might happen in the different phases again with this more complete view in mind. For simplicity and clarity, I will refer to the SMEs, users, managers, interviewees, and so on as the customer. I will refer to the analysis and solution providers as the team.

Intended Use: The intended use may be fairly clear from the beginning, as may be the case when a customer engages a team to provide a known solution. If you want your car fixed, for example, you hire a mechanic to provide a known analysis and solution process. In other cases, however, the problem may not be well defined, and the team can work with the customer to understand and define the problem more accurately and completely. What’s more, ongoing interactions between the customer and team may cause the intended use to be clarified or otherwise modified to add or remove goals. That is, the customer defines the initial intended use, and then the customer and team work together to finalize it.

Conceptual Model: The traditional way of thinking about this involves having the team ask the customer to describe everything they do, to learn the current state. The team then documents the findings and submits the documentation to the customer for review. The customer then provides feedback on what the team got right and wrong, and the process continues iteratively until all parties agree that full and correct understand has been achieved.

That said, the team can (and ideally should) bring a lot of knowledge and experience to this process, and that knowledge and experience can guide the customer to provide a more complete and creative description of the current state. As I have described here, conceptual modeling also involves becoming familiar with tools and solution techniques, market opportunities, and new discoveries which may be leveraged in new solutions.

Requirements: This phase is primarily intended to learn what the customer and all related stakeholders need, but some of the stakeholders in the process involve the team and the prospective solution. That is, depending on the nature of the solution, and especially if the solution is a standard(-ish) one of a type typically provided by the team, the solution, and thus the team, will define some requirements of its own. Moreover, additional requirements may be imposed by governing bodies, (customer and team) organizational practice, and other sources. I have described knowledge teams may (should) bring to an engagement here and here.

Design: The team typically presents a proposed design to the customer, who then provides feedback on its suitability, effectiveness, cost, and other qualities. The customer and team may work together to explore and evaluate multiple solutions. Customers may also solicit designs from multiple teams and then perform their own evaluation and selection. Many combinations and permutations are possible.

Implementation: This one is typically the most straightforward, and classically involves a team implementing a solution for a customer. However, the development, testing, training, and deployment of that solution can be very iterative across many cycles, involve a number of intermediate rollouts, and so on. The implementation and test phases also involve a high degree of iteration and interaction.

Test and Acceptance Testing involves both verification, to see if the solution works as designed, and validation, to see if the solution properly addresses the identified intended use (or organizational need). The team is more likely to oversee the details of verification and the customer will have a larger say in validation.

Many BABOK techniques may be employed during all this review and iteration (think Acceptance and Evaluation Criteria, Observation, Prototyping, Reviews, Item Tracking, and more), but those that involve individual and even small group interactions are primarily interviews. I know I have conducted interviews with almost every kind of worker and stakeholder in a wide variety of organizations and environments all over the world. I have even conducted what are effectively interviews by correspondence (by both email and physical snail mail). The skills I found most helpful are empathy, respect, patience, kindness, clarity, and knowledge of the industry, tools, customers, and methods. Some of those took me far longer to develop than others. Each person will feel more comfortable and excel at different aspects of this process from the beginning, but all practitioners should be mindful of and strive to improve all aspects of this process at all times.

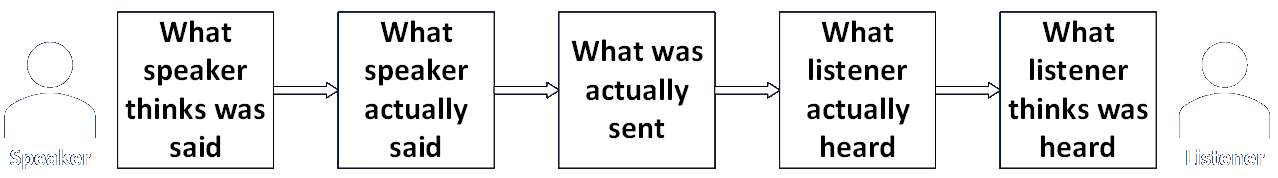

Interviewers should be mindful of all the components of communication shown in the figure above. It takes skill and experience to conduct interviews effectively. However, proceeding in an iterative way that involves review and feedback can help interviewers of every skill level.

Other things to consider are activities that take place before, during, and after an interview. Before activities involve arranging permissions and introductions, setting a time and place, identifying the right people to interview, identifying questions to ask if intending to do a structured interview as opposed to an unstructured one where the line of questioning proceeds ad hoc based on what you learn as you go, sending prepared questions ahead of time, planning how to take notes or record it, and identifying and assuring the required level of confidentiality. During the interview you will want to ensure you remain professional and on track, build rapport, maintain respect, and note any further research of follow-up that may be required. After the interview you’ll want to document what you learned and share it with the interviewee for review and correction, provide your contact information so the interviewee can provide additional information or clarification (or even complaints!), explain how the information will be used (this can be done at the beginning as well), and thank the interviewee for their time and participation.

Interviews have many advantages and disadvantages. Among the more important upsides are the ability to acquire detailed insight from experienced experts and capture a host of non-verbal cues. Some downsides are that they can be difficult to arrange and take a lot of time, especially if many are desired.