During a previously-referenced recent conversation I was asked why I refer to certain research, discovery, and data collection activities as “conceptual modeling.” I do so because it is a surprisingly general standard term of art that has its own Wikipedia entry. From my point of view it especially comes up in the fields of software and simulation design, but it also comes up in the fields of neurological research and philosophy. I encountered the term in formal usage surprisingly recently, when I was using a specific framework for conducting IV&V operations for a Navy simulation product. (It’s amazing how long you can do things and use concepts without formally knowing what they’re called.) There are also a few books (see here and here) that discuss the idea to greater or lesser degrees.

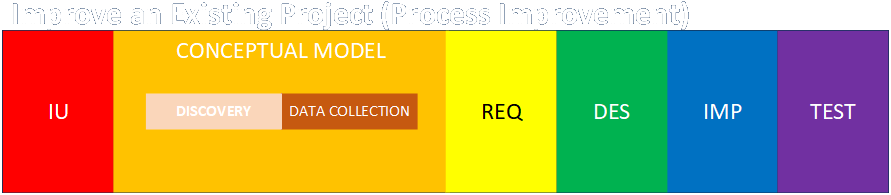

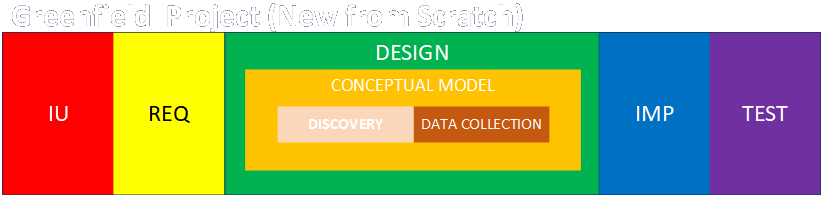

The materials linked above define the term in a lot of ways, but the way I think about it most directly involves the discovery and data collection steps involved in describing the As-Is state and the components that make up the To-Be state. Indeed, the entire design phase can be thought of as a form of conceptual modeling. I usually depict the conceptual model phase as being the second thing we do in a situation where our project will involve modifying an existing system. However, if we’re building a new system from scratch, I describe the conceptual modeling phase as taking place embedded within the the design phase.

Even if the project proceeds from an existing As-Is state, the work done in the design phase still involves a form of conceptual modeling.

Conceptual modeling also takes place at all three “levels” of enterprise architecture, which is comprised of the business layer, the abstract or application layer, and the implementation/deployment layer.

One other form of conceptual modeling takes place when examining opportunities from different angles. For example, becoming aware of a new piece of technology before a project or engagement even starts, and then embarking on an effort to take advantage of capabilities the new technology provides, is a form of conceptual modeling that drives the whole effort, and occurs before it. I can’t say my awareness of an inexpensive turntable device with a hole in the middle of it entirely drove me to identify Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days as a good subject for a college spring carnival booth where the year’s general theme was “Adventure,” but it certainly drove an aspect of the possible implementation that fired people’s imagination and enthusiasm.

If we want to go really wild, devising and implementing and formal test and acceptance process, whether it’s for a CI/CD-type microservices system, a mainframe/HPC system, a desktop system, a distributed control or training system, and embedded system, or even a non-IT solution, can involve a different forms of conceptual modeling.

In short, conceptual modeling involves identifying and incorporating concepts in whatever contexts make sense. That means that the process of conceptual modeling can take place almost anywhere within an engagement or project. It can be one of those very general terms, like “gap analysis,” which can describe any form of identifying differences between where you are and where you want to be (which can also happen within each individual phase and across an entire effort), or “level,” as used in the Dungeons and Dragons role-playing game. There, the term could refer to the power and abilities of the players’ characters; the difficulty and power of magic spells; the difficulty and danger of different sections of a dungeon (or other environment), especially if arranged in “floors” that go ever deeper underground (or upwards in a tower or mountain, or deeper into a dense wood, or…); or even the power of monsters and other opponents. The process of identifying and continually reviewing assumptions, simplifications, and risks and impacts similarly takes place throughout an entire engagement, across all phases in any order.

Revisiting the idea that everything in my framework is iterative both within and between phases, and also the IIBA’s insistence that training materials should never provide prescriptive ways to do things (sometimes to a fault), we see that almost every activity in an engagement can be worked on at any time. I provide a “standard(ish)” order just as a way to start thinking about the entire process. Even if a given project involves doing things in a very different order from how it may often be done, having a standard departure point and template, helps improve the situational awareness of analysts and other practitioners.