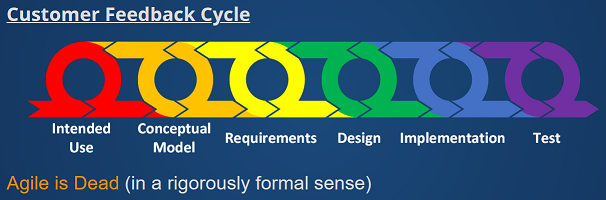

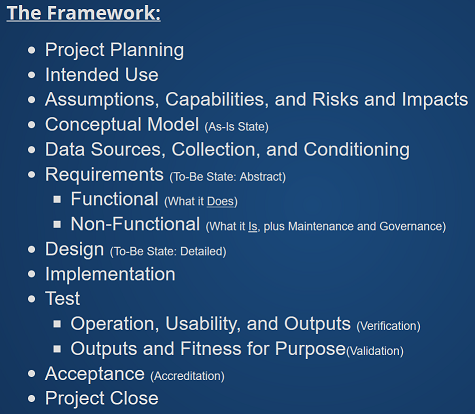

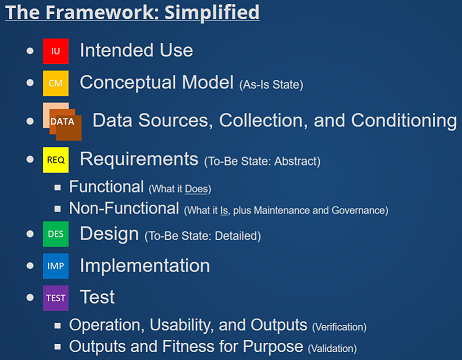

I don’t strongly feature the subject of risk analysis when I talk about my framework, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t accounted for or present. I usually build up my framework like this:

Risks and Impacts appears with Assumptions and Capabilities in the first outline. The reason it isn’t presented as its own phase is because this work really should be happening though every phase in many different forms, and my formulation is meant to provide practitioners with the improved situational awareness that comes from understanding how the phases are truly different. That said, these concepts are called out early because the sooner they are considered, the better.

The practices of project management, Lean Six Sigma, and business analysis both have a lot to say about risk, but the BABOK only obliquely addresses the costing side of things. One thing the project management oeuvre considers, for example, is a way to compare risks by multiplying the cost of the unanticipated or unwanted outcome by the percentage change they will occur. The BABOK includes this idea, but not for evaluating which projects to pursue. Outside of that, however, the practices are mostly similar. (So, should we make the next version of the BABOK even thicker by expanding this section with a lot more detail, especially given the IIBA’s posture of never being prescriptive?)

The first step in dealing with risk is identifying them. Some will be known, some will be unknown, and some will be of indeterminate or variable severity. More information is always preferred, and one way to identify risk is the follow the techniques I recently discussed for the proactive parts of root cause analysis (e.g., FMEA and generally being thorough when examining all parts of existing and new systems and the environment in which the engagement is conducted). Leverage your organization’s policies, lessons learned, and people for all possible insights, and research common occurrences and practices in your region and in your industry. Your organization’s insurers may have further insights to offer.

Risks come in may forms. They can be based on things occurring once, multiple times, or not at all. Events and consequences may map one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-one, so be thorough.

Once risks are identified they should be maintained and tracked in a risk register. It should include information along the lines the example in the BABOK.

- Risk Event or Condition: description of the potential situation that may have to be addressed

- Consequence: what happens if the event occurs or situation arises

- Probability: how likely the situation is to arrive (percentage or something like high / medium / low)

- Impact: the cost of effect if the situation arises (cost, time, materials, people, contract (scope & quality), reputation, or legal explicitly or high / medium / low)

- Risk Level: rough amalgam of probability and impact

- Risk Modification Plan: how the occurrence should be handled (see below in this article)

- Risk Owner: name and contact information of party in charge of managing the situation

- Residual Probability: as above but residual

- Residual Impact: as above but residual

- Residual Risk Level: as above but residual

There are five classic ways to manage risk.

- Avoid: The risk is either entirely prevent or plans are changed so the risk cannot possibly occur (at least in a way that will effect the plans).

- Transfer: The impact of the risk is moved to or shared with a third party (e.g., an insurance company, but could also involve other kinds of teaming).

- Mitigate: Steps are taken to reduce the probability of the situation arising or, if it does arise, reducing the effects or impact of the situation.

- Accept: Deal with risks as they occur, or do nothing at all.

- Increase: Not all risks are negative. Some are positive, and in those cases it may be best to load up on more risk in hopes of a big payoff.

Risks should be reviewed and plans updated at intervals. Some risks are reasonably well understood and quantifiable through actuarial analysis performed on voluminous historical data, known weather patterns in combination with geography, prevailing conditions in industry and economy, and so on, but others are less predictable. The bottom line is to prepare for the expected and to expect the unexpected.