The conversation at the watering hole after this evening’s CharmCityJS Meetup was interesting as usual. In between talking with and encouraging some of the younger attendees and speakers I spoke with a senior developer about a contract he was finishing up in which his ability to generate an effective outcome was severely compromised by the dysfunction and lack of communication in the customer’s organization.

He described how one senior manager worried only about contracts and money and another worried only about lists of work items and there was no communication between them. He also described how no individual or group seemed to be thinking about the architecture as a whole, which included seven different legacy systems talking to one database with no real intermediation or controls. The individual developers kind of did their own thing and changes, without considering their effects from a higher level, often broke other parts of the system. The contractor couldn’t get much in the way of requirements, didn’t have time to map things out and bring order to the system so he could make meaningful headway on his assignments, and tried to communicate the need for some sort of top down organization and communication without success. He talked about how he did his best to mentor the individual assigned to act as ScrumMaster even though he didn’t have the experience or insight to do so effectively. At least that individual asked for help and tried to take advantage of the guidance offered.

I observed that this kind of thing comes up often in organizations in general and in software efforts in particular. A few disconnects are survivable (e.g., the managers of funds might not share all information with line managers and architects) but too many can only mean trouble.

We also discussed some issues we’ve encountered in hiring in the tech industry (a topic I also discussed with one of this evening’s speakers, with a follow-up planned for next week). We observed that the existence of automated search tools gives people the illusion that they can find individuals with long lists of specific skills just because it’s possible to search for them across large numbers of candidates. This illusion leads people to ask for both long lists of skills and extensive experience in many or all of those skills. One need only review discussions on LinkedIn or Quora to get an idea of how this is working out. It’s not that there isn’t a real problem with finding qualified people, there are plenty of job seekers that will, shall we say, pad their qualifications, but what’s missing from many search tools is a sense of context, and an appreciation that certain skills really are emphasized over others when screening candidates. I get a lot of contacts based on misinterpretations of what’s in my various profiles. I describe things in more detail on my website, but even that material awaits further clarification.

The topics inspired me to refer my interlocutor to two resources that seem to say different things.

One was a famous essay in economics about the division of labor in society that illustrates a valuable insight. The essay is called I, Pencil and was written by a gentleman named Leonard Read in 1959. The piece is written in the first person from the point of view of a simple, lead pencil with an eraser attached with a metal band. Picture a standard, yellow, number two, wooden, non-mechanical pencil that can be found all over the world for a minimal cost. What makes the pencil so interesting is the incredible amount of knowledge and number of skills it takes to identify, procure, process, and arrange the assembly of the parts into a single, unified whole. What seems a simple, commonplace object is actually so complex that no one person can ever hope to know enough to produce even a single one from scratch on their own. It takes the cooperation of large numbers of people with specialized training and interests to make it happen. Someone must oversee the final assembly in an organized way, but no one can hope to know enough to do it all.

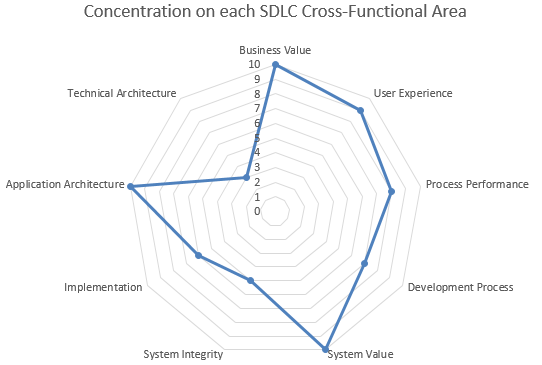

The other resource came from something I learned at an IIBA Meetup in Pittsburgh last June (2017). I described what I learned in this blog post, which involved building teams using members that know something about many things but who know a lot about a few things. More importantly, a team should have a member whose greatest interest and focus is in one of nine different components needed to complete a full Systems Development Life Cycle (SDLC). Again, someone has to be in charge to coordinate the activities, but no one can or should be expected to do it all. I described in the blog post linked just above that my goal is to be an analyst who solves business problems and therefore my interests and passions lead me to concentrate on the nine areas Ms. Hardy described with the following priorities:

I’m no longer trying to be an expert programmer, although I can and do continue to learn new software, tools, and techniques all the time. I’m not as interested in the development tools and deployment and test chains, though I appreciate their importance and try to ensure they are properly looked after by other specialists on the team. I don’t concentrate so much on security because that’s a specialty all its own, though again I want to know it’s being addressed by a qualified team member. I care about the business value, user control of the situation, and that all logical and informational aspects of the process are identified, documented, agreed to, included, verified, and validated. I’ve done that across countless product, project, and program cycles over several decades. I care that the needs are understood and agreed to by the customers, stakeholders, and team members. I work to ensure that everything is mapped, documented, tracked, and communicated in a way that everyone understands. I use pictures and diagrams wherever possible, because a picture is worth a thousand words.

The upshot is that one person can’t do it all, but on a small scale things don’t just magically come together. One a large scale an economy will coordinate itself using the price system without top-down oversight. On a human or organizational or project scale there has to be conscious coordination and review. People with an identified range of specific skills need to be able to cooperate in an environment of mutual respect and support. People need to be trained and incentivized to continue learning on their own.

I’ve seen parts of this done well and I’ve seen it done poorly. My goal is always to ensure it’s done well, but doing so requires clear communication, time, and realistic expectations. If you’ve got time to fail or time to do it over, you’ve got time to do it right in the first place.

Try to do it right in the first place. Ask me for help if you need it. 🙂